Outside Director Lessons #3: How Suddenly Companies Can Collapse!

As its sales increased, Alps had financed its growing working capital needs by borrowing from banks. But no bank wanted to be a “main bank” for a small unlisted company any more. So every year or so we added another bank lending us 200 million yen or more, until we had something like six or seven different banks. All of these loans were short-term, and had to be “rolled over” each year.

As long as all the banks rolled over their loans each year, and we were able to find a new bank when we needed it, to the board, everything seemed fine.

But the reality of the book business was that publishers of map books did not really “sell” their books to book wholesalers outright. Publishers actually sold almost all of their books on a sort of consignment basis. In this system, Alps booked revenues when they passed the books to wholesalers and bookstores, and a booked reserve for the percentage of books that historically had been returned unsold, assuming it would remain roughly at the same level.

It took a long time for books to return unsold, – that is, for us to know that they were not selling. When the actual percentage of returned books increased, the amount became larger than our reserve, and we had to start reversing (reducing) our accounting revenues by the excess amount.

This situation scared the board, which suddenly then asked me to ask Yahoo if they still wanted to buy the company. Yahoo of course replied that it had no interest to buy the company at that time. Alps had told them “no” once before. Why had it suddenly changed its mind? They could easily guess that the company was in financial trouble, and could anticipate what would happen next.

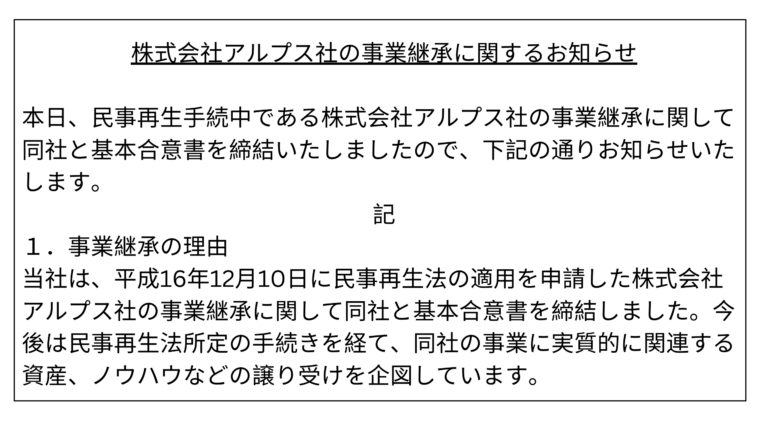

Alps was suddenly forced to declare bankruptcy, wiping out stockholders’ equity and the banks’ loans. Alps had to immediately look for a “sponsor” under the “minji-saisei” (civil rehabilitation) system. The company that immediately stepped up with great interest to be the sponsor of Alps, of course, was Yahoo. There had been few very logical buyers in the first place, something that had always bothered me. In M&A, you need (a) remaining value and (b) competition between buyers, to do a good deal. No matter how hard I tried, I had been unable to communicate this reality to diligent map experts who did not understand M&A transactions.

Yahoo immediately became the sponsor, thereby acquiring all of Alps valuable map data, its domain knowledge, and its employee contracts, for a price of zero Yen… and without having to take on any debt at all.

The moral of the story? Most Japanese companies and their boards tend to avoid selling non-performing business units, subsidiaries – or the whole company – until far too late in time. Executives and even other outside board members often feel it is somehow disloyal to not give the business a bit more time, or to move quickly to “sell” their employees. But in M&A, if you do not move fast to sell a division or a company while it still has value, you often discover later on that there is very little value left, and very few interested buyers. “Very few interested buyers” almost guarantees that you will only get a low price, if you can sell the company at all. As a director, I should have fought even harder to explain this. Actually, I thought I was fighting hard, but at the time, I had no war stories like this one to tell.

Another lesson is that it can be worth it to pay higher interest for long-term debt from a main bank that might help you convince the board because it has a larger amount at stake…and conversely, if you cannot find a long-term lender like that, you should be worried. Last, MapInfo was not as helpful as I would have liked, because if anything they wanted to delay booking a loss.

Nicholas Benes

(writing in his personal capacity and not representing any organization).

I am able to talk about what happened at the Alps Mapping board meeting because the company no longer exists. Normally, directors have a duty of confidentiality to the company, and that duty continues until their death with regard to board discussions and confidential matters. However, since Alps no longer exists, the company to which I owe that duty no longer exists.

If you thought this post was helpful, here are many other posts in this series, which will continue! Please come back for more.

Outside Director Lessons #1: Genesis of Director Training Nonprofit BDTI

Outside Director Lesson #2: My First Experience as an Outside Director

Outside Director Lessons #4: What is Worse Than the Company Going Under?

Outside Director Lessons #5: Being a Whistleblower Hotline

Outside Director Lessons #6: Insist on Total Independence!

Outside Director Lessons #7: If No D&O…Get It Yourself

Outside Director Lessons #8: The Role of the Board

Outside Director Lessons #9: Appointing the CEO